"We Showed Them What Could Be Done"

How a campaign to re-open a neighborhood park helped build small-town political power in Oxford, North Carolina

Jason Dunkin lives out in the country on the same small bit of land he grew up on.

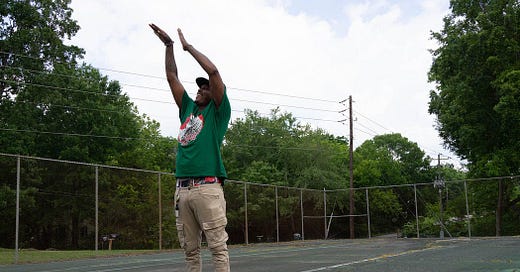

The rain is beating down hard on the metal roof. He looks out the window towards the road. “I remember my dad and my uncles would pick me up from right here,” he gestures to the house around him, “to go play ball.” He smiles at the memory.

They’d go about 15 minutes up the road to Oxford, North Carolina. They’d drive the car into town on Broad Street, passing the barbershop and downtown, until Broad turns into MLK Jr. Avenue. Then they’d hang a right to get to the Granville Street Park.

“Everyone would gather there,” explains Jason.“Teenagers who came to play ball would bring their younger siblings, so the park was just full all the time.”

But today the park is empty. The basketball hoops are gone and the blacktop is cracked. Heavy rain has muddied the ground and water pools over the sidewalk.

There’s a small sign, though, stuck in the grass. It’s a little crooked, a little beat down by the rain, but it reads “Park Renovations Coming Spring 2024.”

The story behind that little sign is a story of really, really good organizing.

“We always had a sense of pride here,” says Keisha Tyler about the area around the Granville Street Park, which sits at the center of the thriving Black neighborhood she grew up in. “There was a real sense of community and making sure that the community was kept uplifted. People got together, they had meetings and it was a really nice place to be.”

In the 1990s, however, Oxford began to cut back on city services. Politicians reduced taxes on the wealthy while leaving local budgets unfunded, including the budget for the park.

As municipal budgets decreased, people struggled to make sense of the town’s neglect of the park. One narrative, spread by the town’s white politicians, was that the Granville Street Park was dangerous.

“It’s just urban legend,” says Chelsea Smith, who also grew up in the area. “We did have adult guys starting to come down and play basketball. And I’m not going to say there was never a fight or a pushing match or something like that, but dangerous? No. And the politicians and media just really played it up.”

“The negative stigma they put on it was so they could take it away from us,” explains Jason. “They made it sound like it was all drugs and fighting when we were just playing ball. Putting a stigma on the park put a stigma on the whole community.”

And so the park fell into disrepair. The beloved basketball hoops were removed, the pavement cracked, and weeds grew up everywhere.

“I thought that the park was doomed to be like this forever and that we would only have stories to tell our kids about how the park was,’ says Keisha. “It’s been dead for about 20 years.”

During those years, community members who lived near the park quietly minding it and looked for ways to bring it back. But they knew it would take a larger effort to get the town to fund it again.

In the spring of 2023, local Down Home North Carolina members saw an opening. They discovered that $2.8 million was left unspent in the Oxford American Rescue Plan (ARPA) funding., In addition, the Oxford City budget had a multi-year surplus of roughly $7.5 million.

Surveying the community, members learned that most people did want to see the park revitalized. “You always felt,” explained Jason, “That the lack of investment wasn’t just in a park, it was a refusal to invest in us, the people.”

They centered their sights on the city budget-making process. By knocking on doors and circulating a petition about making the park a budget priority. They asked people not only to sign the petition but also to join them.

Chelsea set up a meeting with the City Commissioners office. “They only wanted four people to come in,” she said, “[But] we had about 20 people!” All summer they kept it up. They held meetings and small events. They became regular fixtures at town meetings.

Finally, on Tuesday, September 12th, the Oxford City Commissioners voted unanimously to refund the Granville Street Park.

Chelsea, Jason, and Keisha describe the Granville Street Park as something more than a park– it is a bigger representation of a people, a culture, and a place. It is not surprising, then, that the movement to get the park refunded also became much more than a campaign to reopen a park.

“We saw what we could do through organizing when we didn’t have any real strong connections in local government,” said Jason. “Imagine what we could do if we have our folks in office?”

Soon after the park funding was secured, local Down Home members endorsed three local candidates in the upcoming municipal elections: Steward Powell and Curtis McRae each for Oxford Town Commissioner and Guillermo Nurse for Mayor.

All three are Down Home members and all three were well-known, hometown guys– which matters in a place like Oxford. Jason has been to church with Curtis; Stewart’s mom was his school teacher. Guillermo Nurse had flipped burgers on the grill during one Granville Street Park campaign event, and Stewart had helped knock on doors.

“We had shown the community what can be done,” explained Jason about the park. “So we could now go back to people and tell them what we could do next.” The park gave people a taste of what was possible.

Down Home Granville’s massive electoral canvassing paid off: Curtis McRae was elected to the Commission, while Guillermo Nurse became Oxford’s first Black mayor.

Meanwhile, construction at the Granville Street Park has started. The park’s trees are protected with caution tape, rusted playground equipment removed, and the park is ready for its much-needed upgrade. Springtime is just around the corner; you can almost hear friends chatting, kids laughing — and a basketball being dribbled down the court.

“This is our community,” says Chelsea. “We are community strong. We’re Granville Street strong. And I’ll testify that to the highest mountain.”