Something beyond a meal.

Jocelyn Smith and her friends are providing free meals, sure, but its deeper than charity.

When I was in high school, my favorite teacher announced a volunteer trip to a local soup kitchen. I signed up immediately, excited to see my peers outside of the classroom.

We assembled at the Raleigh Rescue Mission and were asked to line up along one side of a row of folding tables to serve food. For an hour we greeted the men and women who came for the meal, dishing mashed potatoes and cornbread onto their plates as they moved down the line.

A few weeks later, my English teacher asked me to write an article for the school newspaper about the poverty we had seen. I can’t remember what I wrote.

This was years before I, as a young single mother balancing work and school, would have to sit in a long line waiting for my number to be called so that I could speak with a caseworker through Plexiglas and recertify my food stamps every six months.

My high school had taught me to be on the “giver” side of the table, ladling carrots across to people in need. But motherhood was putting me on the other side, sliding my ID and documents through a small window to show that I was working so I could get $100 a month to buy fresh fruit for my child’s lunch.

Most of us don’t permanently live on one or the other side of that long table, but give and take, need and have the ability to share, at different times in our lives.

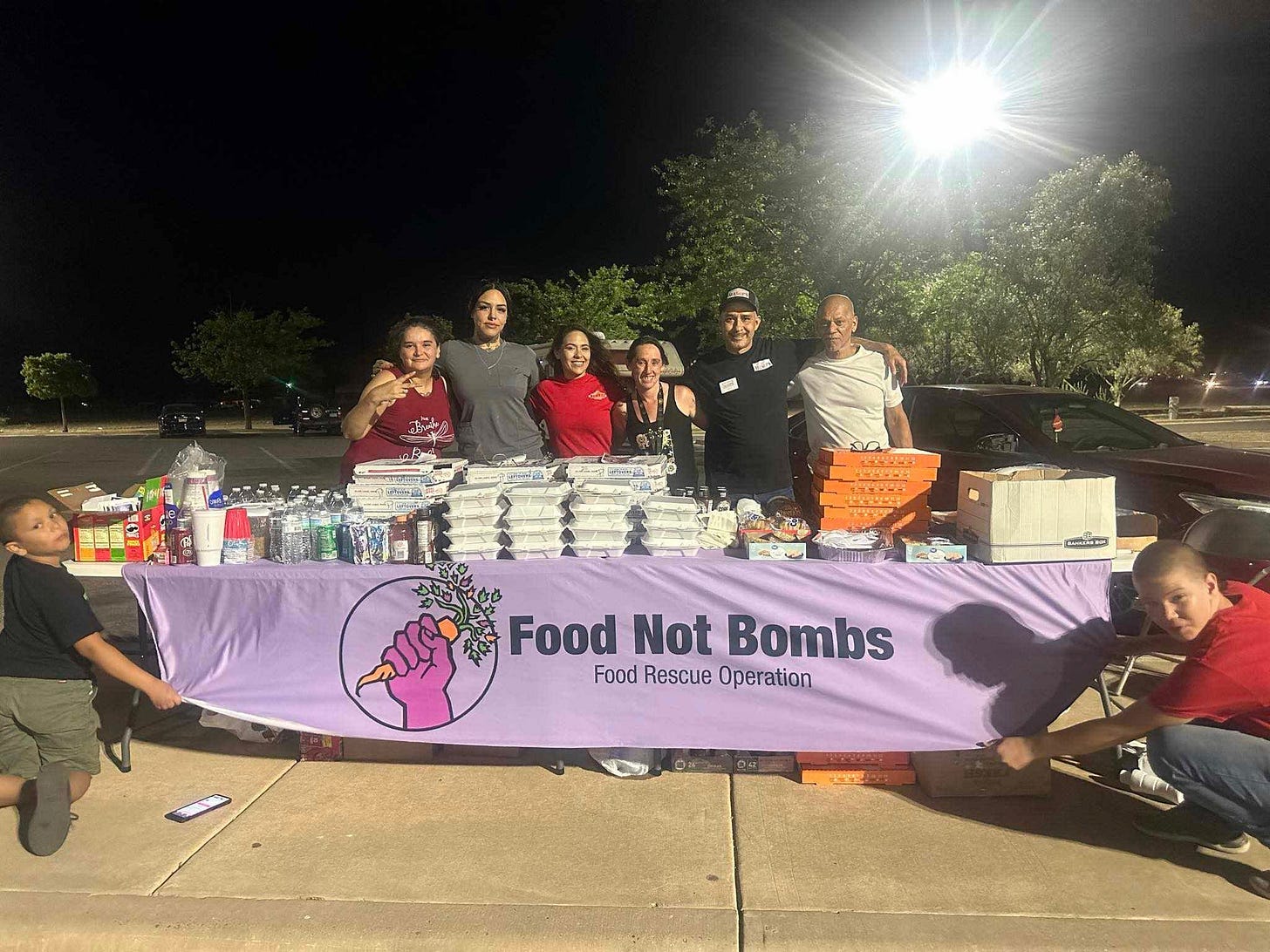

I recently connected with Jocelyn Smith of Roswell, New Mexico, who twice a week serves free meals to anyone in need, no questions asked. She’s a mom and works at a local radio station, but when she’s not at work she drives around town picking up leftover food from restaurants, events, and the local middle school. She and other volunteers then prepare that food and serve it at Pioneer Plaza downtown. Jocelyn says that thirty to forty people show up for both the Friday and Sunday meals.

I wasn’t surprised to learn that Jocelyn also sometimes needs help. While she’s spending hours every week collecting, preparing, and serving food to her neighbors, she also receives SNAP to help support her own family’s nutritional needs. Jocelyn is by no means an anomaly. In my experience, many, if not most, people doing on-the-ground work helping work in their communities are not doing it because they are well-off themselves, but because they understand the need.

When I asked Jocelyn why she spends so much of her week serving others, she shrugs and says: “Because I get it.”

Getting it matters. When people who “have been there” (or even “are there” right now) help their community, they typically approach it through an organizing lens instead of a charity lens. In other words, they understand that they are not serving across a table but sitting at that table with people with whom they can build a better future. At the Roswell meal, the difference is clear: Jocelyn recently posted a video of people eating together and dancing to the 1966 hit “I’m your puppet” playing from a speaker on the sidewalk.

In other words, what Jocelyn and the others are creating in downtown Roswell is something beyond serving a meal.

For years, I worked at a large regional food bank that moved literal tons of food every day in and out of its big warehouse doors. While the organization was grateful for– and relied on– its wealthy, philanthropic donors, it was largely poor and working class volunteers that were distributing the food into their communities through a network of small churches and community centers. The volunteers at these distribution sites would frequently pack up a small bag for themselves at the end of the day or grab fresh vegetables for their aging mom, stretched-thin neighbor, or down-on-their-luck friend. At one food pantry in Statesville, NC, there was a woman in a wheelchair who would come to get a bag of food for herself each week, but she’d also bring two Ziplocks of cat food and a can of soup to donate.

These volunteers, Jocelyn, and this woman with the cat food and soup are essential to this work. Not only are they deeply knowledgeable of and connected to the communities they help, but they are also correcting the narrative that poor and working people are either the objects of pity or, worse, freeloading off others' goodwill. They are showing, instead, that they are part of the solution.

When we believe that our world has just two sides to a table or is a set system of haves and have nots, of givers and receivers, of winners and losers, then not only are we missing the tremendous resiliency and mutuality of poor and working communities, but chances are we are also shooting ourselves in the foot.