From the Ground Up

With $40,000 and some elbow grease, local residents in Roswell, New Mexico, create an out-of-the-box solution to the local rental crisis

In many ways, the house is like many others here, with a pitched roof and one window on each side of the front door, a bit like a child's drawing. A tall metal sunflower is in the garden bed, casting its shadow across the sandy desert yard.

The Deming Street house is small and modest in a line of small and modest homes. You could drive by without noticing it. But it wasn't long ago that this house sat empty in a town long troubled by a housing shortage and homelessness. Its vacancy stood as a jarring reminder of the disconnect between the people living in hotels and cars and the ability – or perhaps will– of Roswell, New Mexico, to find solutions.

But today, the home's freshly painted shutters and trim, the new blinds in the window, and the car in the driveway are all indicators of not just occupancy but change. And how that change is coming about reminds us all that the people closest to a problem—the poor and working-class people who make up our cities and towns—are the ones who most often hold the solutions for the troubles in their hometowns.

Nicole Scarpa and her children had only been living in the Town Plaza apartments for a year when the building was condemned. The out-of-state LLC that owned the building had failed to make repairs, and Nicole and her neighbors didn't have hot water, amongst other dangerous problems. Nicole was given seven days' notice to move and didn't get her deposit back.

Many of the sixty displaced families from Town Plaza moved into motels. However, Nicole dug through the Roswell Daily Record for rentals because she knew that so many people looking for housing at one time would be a big problem. "I didn't want to be in competition with my neighbors for a home, but that was what was happening."

Houses– and specifically rentals– are hard to come by in Roswell. Once home to a thriving military base, Roswell's 1960s heyday is past, and much of the city's housing stock is old and needs repair. Most rentals here are single-family homes and are increasingly rented to oil field workers and traveling nurses who can pay prices that locals simply cannot. Apartment complexes are few and far between due to the city's restrictive zoning ordinances. A developer hoping to build affordable units has been turned away twice in as many years.

"There's a disconnect with the people in power in this town and the people who live here," says Jocelyn Smith, who had a friend who was homeless who would shower at her home before work. "They don't see how complicated this situation is for everyday people. My friend was paying $100 application fees to places that also required a deposit. When she didn't get the apartment, she wouldn't get the application fee back and had to save up again to apply at the next place. She was shedding money."

Rents are high and disproportionate to local wages, says Kerry Moore of the Chaves County Health Council. Her organization operates the local 211 hotline and the vast majority of calls it receives are from Roswell residents needing help with rent or utilities.

"There's an idea here that everyone who is struggling or homeless is somehow an outcast, and there is nothing to do for them. What they can't seem to wrap their head around is that the people caught in this housing crisis are literally their own employees," she says of the city's inaction around the crisis. "It's their public works employees, their city workers, teachers. The hiring rate for local police is just $17 an hour. You certainly can't buy a house with that income, and you can barely pay rent."

"Roswell is like an island," says Kerry, "and its inhabitants are left to figure out everything on our own."

After meeting with elected leaders to find solutions, going to city council meetings, and even hosting a town hall where community members asked their elected leaders and candidates running for office how they would address Roswell's housing crisis, local residents felt frustrated.

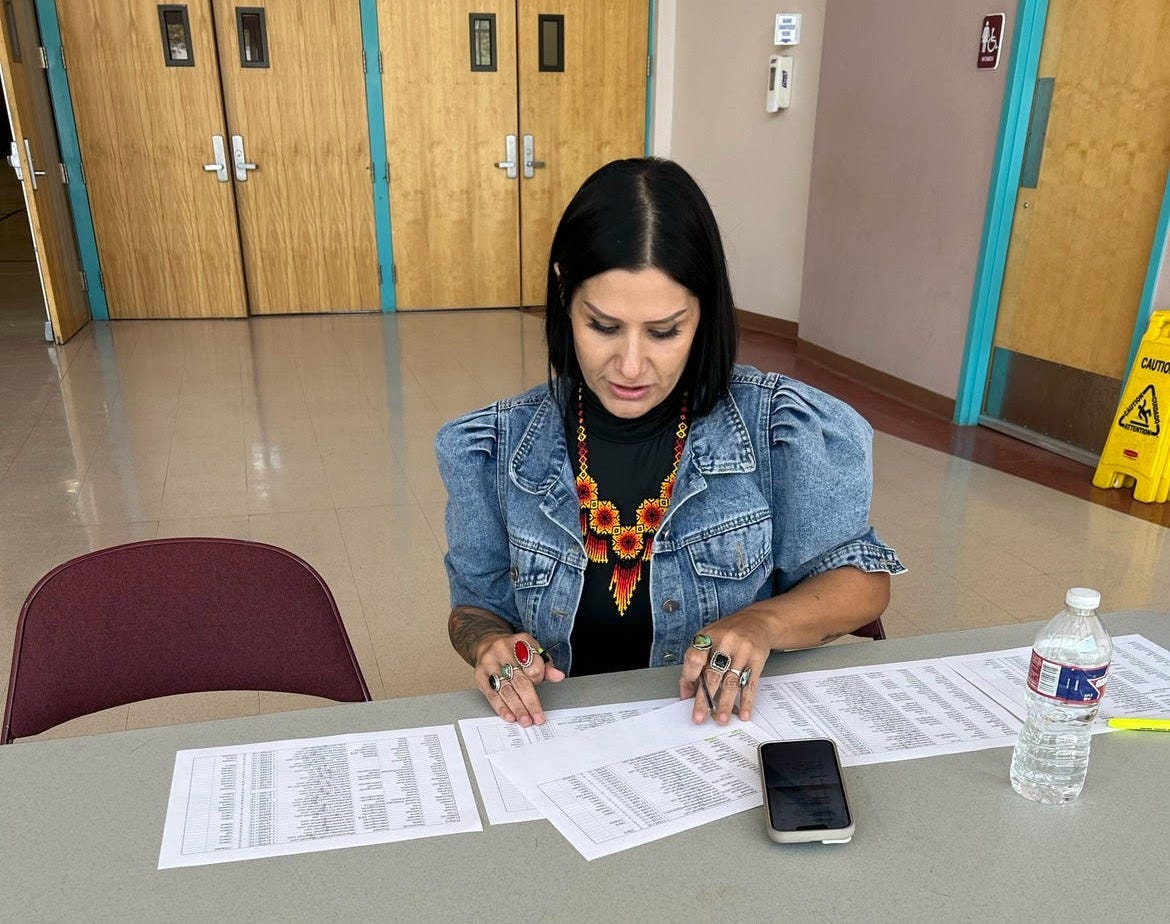

Jeneva Martinez, founder of the Roswell Homeless Coalition, who had helped open two homeless shelters and a warming center, tried to secure funding or support but repeatedly ran into red tape. "There is a lot of NIMBY-ism here," she explains, "And this idea that this isn't a government issue, but something for charities to take care of is very frustrating."

Locals, like Jeneva, were delivering tents and sleeping bags to encampments. Nicole was researching city-owned condemned properties to see if they could be rehabilitated. Jocelyn was serving a free meal downtown twice a week. Kerry and her organization were addressing health needs.

"We were all doing good work and trying so hard, but we needed something out-of-the-box, something that went around the red tape and could make a long-term difference going forward."

The group called themselves "With Many Hands" and began knocking on doors, talking to Roswell residents, and getting their ideas for solutions. After all, who knew this better than their neighbors, many of whom lived one paycheck away from being homeless themselves? While they did this work, going door to door through the neighborhoods south of Second Street (the North/South but also the economic dividing line of Roswell), they realized how many existing houses were boarded up and unoccupied in Roswell.

After some research and many conversations with neighborhood people, they learned that local families owned a large number of Roswell's empty houses. "Sometimes, they had inherited the house from a relative, or maybe it was purchased for a family member who no longer needed it," explains Jeneva. Most of these families wanted to rent the house for a little extra income, but repairs were needed to get it back on the market."

Jocelyn remembers driving around town looking at empty houses. "We'd be going up the street, peeking at the buildings, checking how bad they were. Did the house need an HVAC repair, or was it about to fall down?" They learned that most of these homes needed something small– some flooring where the plumbing had leaked, for example. These repair costs were out of reach for the property owner but within reach of a community effort.

That's how Rehab2Rental was born. After securing $40,000 in seed money, Jeneva started calling the families that owned these vacant homes.

John Surgett and his wife had lived in that little house on Deming Street years ago when they were starting their family. Even though they eventually moved to another neighborhood, they still knew all their Deming Street neighbors. After years of renting the home to firefighters ("One would live in the house, and when he moved, he'd refer the next guy," says John), the old house was worn down and needed repairs. John was making those repairs as he could so it could be occupied again– but it was taking time and money he didn't have. The house sat empty amid a housing crisis.

"It was God's work," John says, describing how a young mother reached out to John asking if he had any places to rent right when his wife saw a With Many Hands Facebook post. With a $10,000 loan from Rehab2Rental, John could finish repairing a room in the Deming Street house and fix worn trim on the exterior.

Rehab2Rental made these small loans to four local property owners. Those property owners then used local contractors to make the necessary repairs to bring the homes up to HUD rental standards. They can repay the loan over two years or rent the house out at Fair Market Value so a family with a HUD voucher can immediately move in. John and all the other property owners chose the second option to keep rents low.

"It was an easy decision," said John. "I care about this community and want people to have homes. That helps me, it helps a family, and it helps the community."

"There are other ways to be paid than with money," John reminds us. "Relationships are important, too."

Because local, working-class residents who knew their community inside and out had worked together to source a simple, out-of-the-box solution, Rehab2Rental put four families into four homes in two months in Roswell, New Mexico.

"This model is simple and replicable," says Jeneva. "Because we are all from here and put our heads together, we figured out something that can work." The pilot project for Rehab2Rental has now been awarded an additional $500,000 grant from Housing New Mexico to complete 18 more homes in Roswell. "The program is a win/win for the property owner, the renter, the neighborhood, and Roswell."

Jeneva feels confident that With Many Hands has unlocked a winning solution for Roswell but points out that the town needs a "full spectrum" of housing resources. "To have a healthy community, we have to have emergency sheltering, transitional housing Section 8, Senior Housing, workforce housing, and affordable housing," she says. The goal is to have poor and working-class people at the table when the city revises its master plan.

The With Many Hands team is gearing up for the next round of Rehab2Rental repairs. They are also out in the working-class neighborhoods of Roswell, knocking on doors again. With municipal elections later this year, they are asking their neighbors what issues they want the candidates to address. The residents of Roswell have shown the city what they can do, and now they want to see what the city can do for them.

They have, after all, shown that they are worth their salt.

Gwen, you are doing such excellent work with this series.

I’m curious if there is an agreement in place about the rental rates after the loans.