Bad Water

You can't drink the water in Three Rivers, Michigan, without risking your health. Now, residents are organizing to make sure their local government cleans up the mess.

Vernis Mims is a dad– of a teenager, nonetheless.

He’s also a basketball coach and has worked for years as a substitute teacher. In other words, he knows a thing or two about kids.

He’s known many of the children in Three Rivers, Michigan, since they were babies. He thinks a lot about what kind of future kids need but also about what they need right now.

So, when the mayor of Three Rivers told Vernis and his neighbors that it would take 20 years to fix the dangerous, toxic water in their small Michigan town, Vernis knew these children couldn’t wait that long. “Their whole childhood has passed by at that point,” he says. “It’s our job to care for them and do right by them now– not later.”

“We made it clear to the city that they’d better re-think that plan,” Vernis says, laughing.

And they did.

Three Rivers sits at the confluence of the St. Joseph River and two tributaries, the Rocky and Portage rivers. With just under 8,000 residents, Vernis describes it as “your typical midwestern manufacturing town” where many locals work in the trailer factories or a container plant. Nearly thirty percent of the town’s population are children.

Three Rivers exists because of the rivers, but the water is also the trouble here.

Gina Foster has replaced all the pipes in her house, but the water in her bathtub still runs brown. Her family has lived in Three Rivers a long time– back to the 1960s– and there’s even a park named after her cousin up the street from her house. The water wasn’t always bad, she says, but for the last decade, something has been wrong. Gina has replaced a water heater, filters, pipes, and humidifiers in her home. “They’d get some much grit and dirt in them, they'd just break down.”

“We’ve known for a long time that water here is no good,” she says. “Sometimes it stinks so bad it could make a buzzard gag.”

Three Rivers’ water is provided by the municipal government. But when Gina went to talk to the city, they told her to check her pipes– the ones she had already replaced.

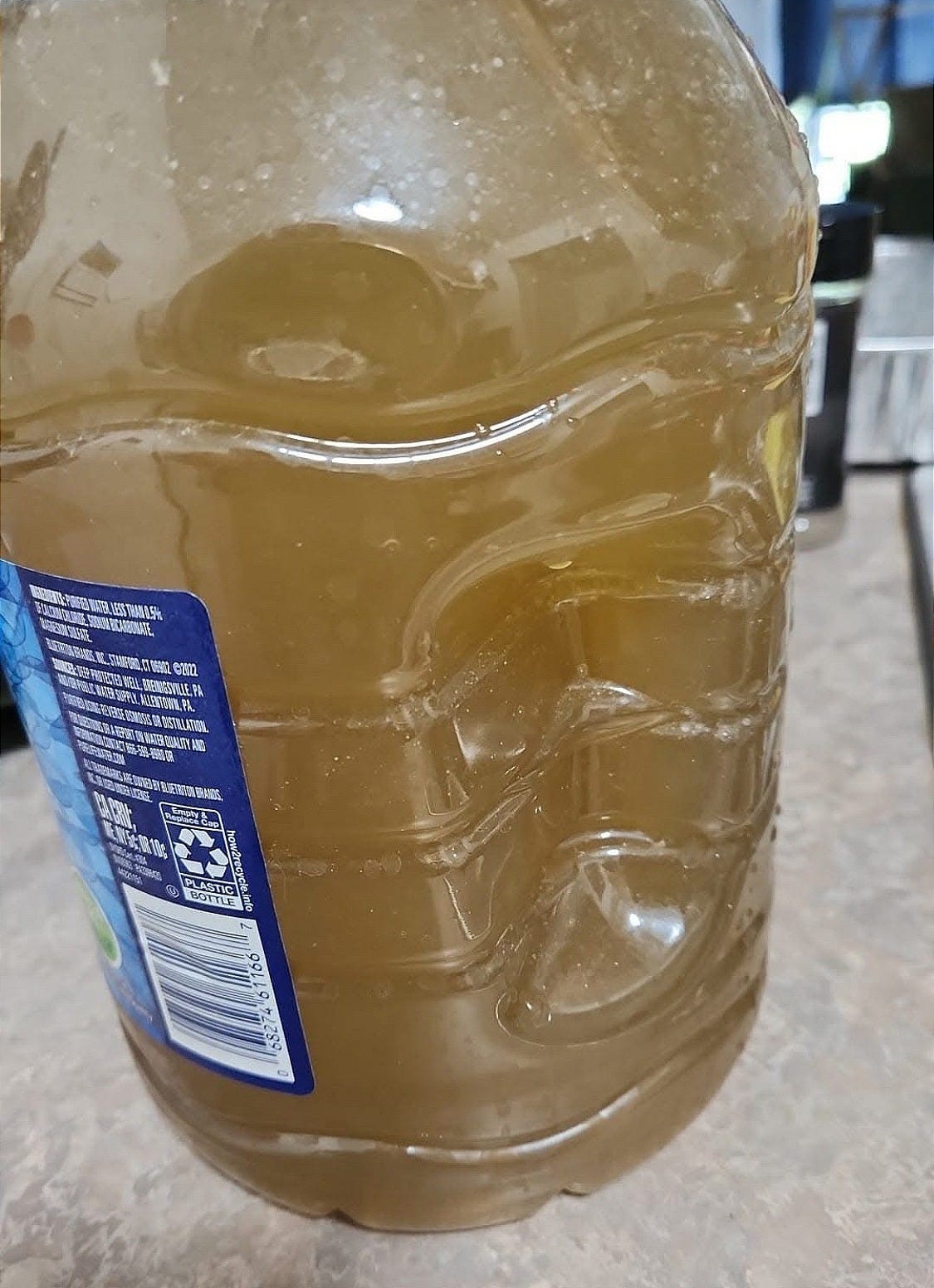

Gina wasn’t alone. The dirty water was quickly becoming the talk of the town. On Facebook, people posted pictures of the cloudy, discolored water that was coming out of their taps. Neighbors talked about rashes and skin problems and wondered if the water was to blame.

Still, they could get no answers. “We had this bad water,” explains Gina, “But the city always had a counter story to make you feel stupid.” Again and again, Gina and her neighbors were told to let their pipes run or call a plumber to make repairs.

In August 2023, nearly eight years after Gina replaced her pipes, a Public Health Advisory was issued in Three Rivers. The notice read that the levels of lead exceeded 15 parts per billion, making it unsafe to drink. “It’s not like we were surprised,” says Gina. “We knew our water was nasty.” You can practically hear her roll her eyes.

It was determined that it was the city’s service lines that were feeding lead into the houses of Three Rivers – not the homeowners’ pipes.

The Health Department began distributing filters, but not everyone qualified for one, explains Casey Tobias, who has lived in town almost thirty years. “They were prioritizing people with children,” says Casey. “I get that, but doesn’t everyone need clean water– at least last time I checked?”

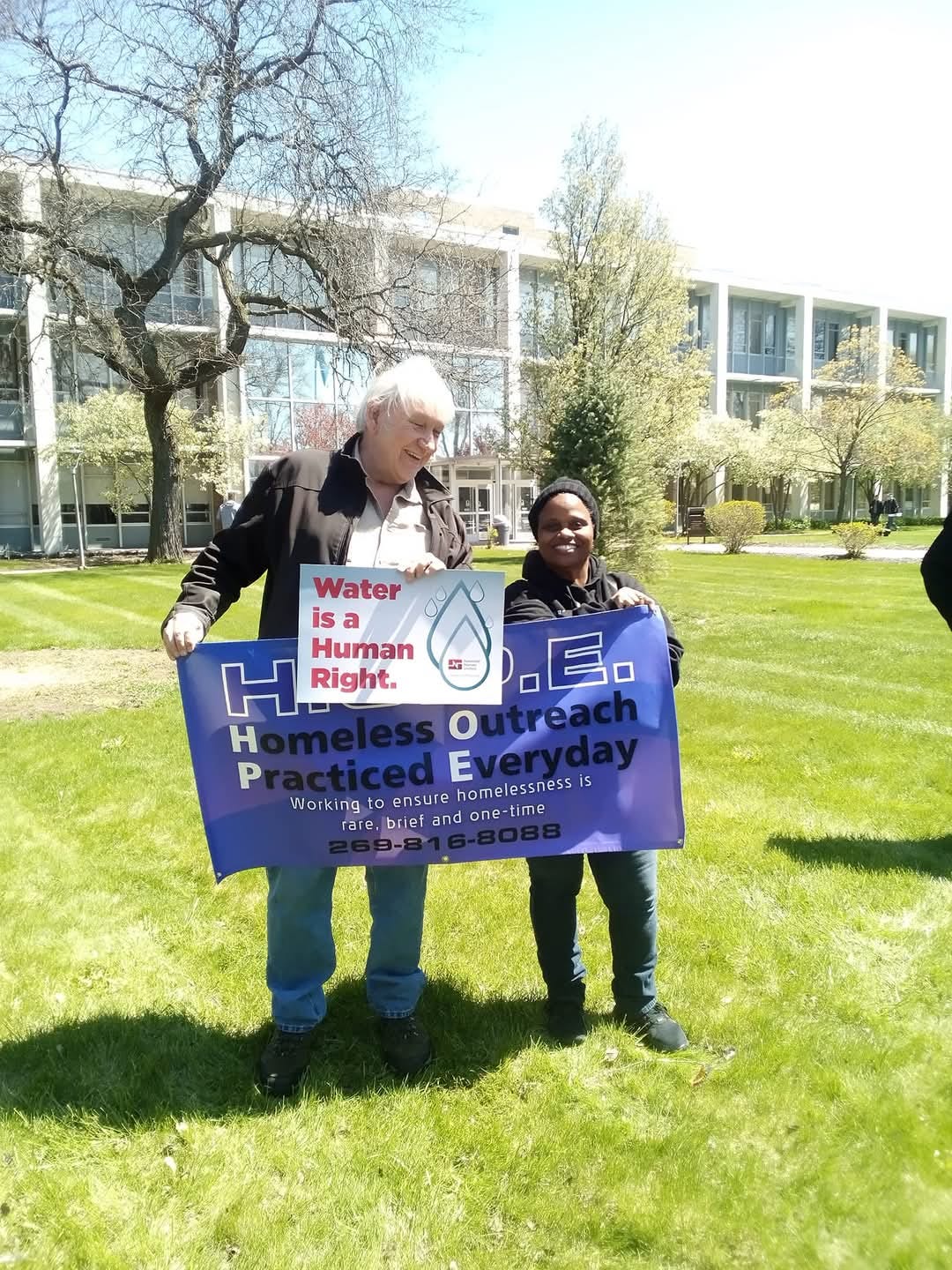

Plus, Casey noted, not everyone could use a filter. “We aren’t a wealthy city– there’s a big homeless population for a small town. For example, people living outside have to go to a store’s bathroom to get water. They can’t use a filter.” Casey, who worked for years at a gas station, said that it was common for people to come to the station to fill up water bottles.

“And filters aren’t an actual solution,” adds Gina, even for those with homes. “What are we going to do, fill up a pitcher, wait to let it filter, and then pour it into our baths? Filters can’t be an answer forever– we need something more than filters!”

Gina stopped drinking her water and began paying $100 a month to buy water at the store. Vernis was having his family brush their teeth with bottled water. Casey was filling up jugs through a filter system and dropping them off around town. Meanwhile, the city raised the water prices– not once but multiple times– saying they had to increase the cost to make the necessary repairs.

Casey knows about helping people in a pinch. She and a large team of volunteers operate HOPE- Homeless Outreach Practiced Everyday, which provides food, clothing, tents, transportation, and other basic needs to families in town. In this way, she’s familiar with how to triage the various crises of poverty, but the water problem was bigger than she and her volunteers could handle. “Maybe some people in this town can afford buying filters and bottled water as a way of life, but most of us can’t. I felt like no one was caring for the least of these. This was a system issue- not something that people could handle on their own or even a group of volunteers could handle. We had to figure out how to get our government to change things.”

“The government should have known about this issue before it got so bad,” says Vernis of the local elected officials. The mayor and the town manager have both been in office for nearly thirty years. “This didn’t just pop up as an issue. It’s been building up. After all, water comes downhill from everything else.”

“We weren’t getting any traction by just complaining,” Gina says of the Facebook posts and the calls to the city’s water department. “So we had to figure out something else.”

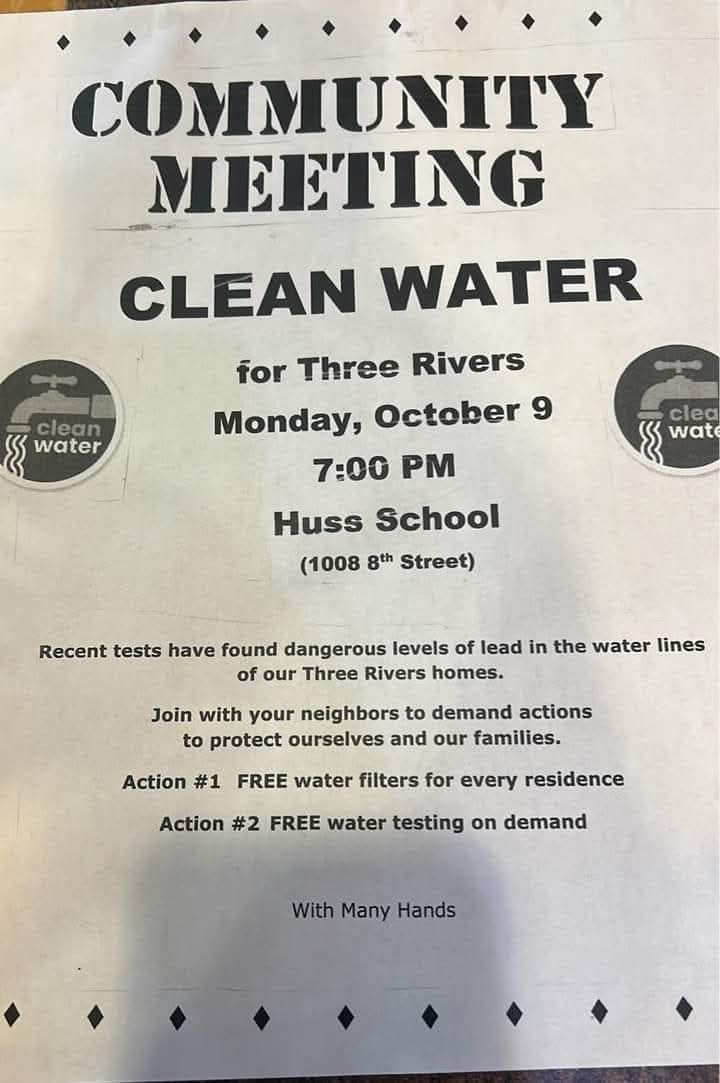

That’s why she invited a few of her neighbors to go with her to a meeting that was called by residents to talk about the water. In September 2023, about thirty people gathered at the Huss Center, a community center in the Second Ward where Gina lives. When the group decided to form a water committee, she signed up.

Casey also jumped in. She mobilized HOPE volunteers to start knocking on doors to talk to residents about the water situation and ask them to get involved. Within a few weeks, the original group of thirty had grown to about 100 more.

By October, the Three Rivers Clean Water Campaign was ready to show up at City Commission – this time not to complain as individuals but to make a demand. Through their on-the-ground organizing and public forums, they had surfaced a lot of concerns in Three Rivers– issues of transparency, communication, and representation. Some people wanted to take on the whole system, but the group decided to stick to one demand and one talking point: Fix the lead lines.

The Three Rivers Clean Water Campaign stuck to that simple message– speaker after speaker asked the city to replace the lines. Casey and her volunteers continued to go door to door, inviting more people into their growing movement. “By the November Commission meeting, over 50 people showed up to speak,” says Casey. “There were over 80 minutes of public testimony and demands.”

Gina became a regular fixture at the city meetings. “It’s true- I’m going to run my mouth. I decided I’d make a stir every month if I had to.”

Maybe because the comments were so plentiful and the pressure so intense, the city stopped livestreaming their meetings, as had been their custom before.

“People from all over were getting involved,” says Casey, describing a picket they held outside City Hall. “We were offering an opportunity for them to do something together instead of just being frustrated alone. We hand you a placard and a marker to make a sign; all you have to do is show up. And they did!”

Meanwhile, Vernis– who had been emceeing many of the community meetings– had another plan: He decided to run for Mayor. Municipal elections were underway, and Vernis saw a chance to force the candidates to address the water issue instead of sweeping it under the rug. He ran his campaign around clean water, insisting it was a human right and a responsibility of the local government.

“I believe they knew the water was the number one issue,” Vernis says of the local incumbents. “They didn’t not understand, but they hid behind politics instead of stepping up and out to figure out a solution.”

“They kept saying, just wait, it’s a process,” says Gina.

“I mean, right,” says Vernis, clearing his throat. “I understand a process. I understand how it works, but I don’t like it. Nobody cares how hard it is– it’s the government's job to fix it.”

Soon enough, the Three Rivers city government began to change their tune.

Gina thinks the turning point may have been the outside media. Local newspapers and TV stations from the surrounding area began to run articles about the lead in the water and the organizing they were doing. She remembers feeling the room change when the press showed up. “It was like they were now going to take us seriously,” she said.

Casey says she felt a shift when volunteers launched another door-knocking campaign in the summer of 2024, circulating a petition asking the EPA to get involved. “We knew that the City government was aware we were out there getting hundreds of signatures. We were everywhere.”

Others think it could have been the fact that Melissa Mays– a mother-turned-activist who sued the City of Flint over their water crisis- came to town to meet with local residents, drawing the connection between what was happening in Three Rivers and what happened in Flint.

Whatever it was, by September, the City had signed an agreement with the EPA, accelerating the lead line replacement to be completed in 18 months…. A far cry from the original 20 years.

That feels much better to Vernis Mims, whose daughter is now fifteen. Perhaps before she is grown and has moved out on her own, she can drink a tall, cool, clean glass of water from his kitchen sink.

A new year has come, and now it is Spring; soon, the serviceberries and dogwoods along the rivers will start to bloom. Vernis, Gina, Casey, and all the others who worked on the Three Rivers Clean Water Campaign are waiting- and watching– for the water in their pipes to run clear.

It’s still brown. They still drink bottled water, but, as Vernis says, they hope the agreement will work and the pipes will be replaced soon.

Gina is eagerly awaiting to see the old pipes on her street dug up— but she worries that these poorer parts of town might be done last. “We are watching them, but now we know what to do if they don’t do us right. You’ve got to keep on them like a cat on a dog,” she laughs.

Still, as they wait, they are each proud of what their community did; proud of the long hours in organizing meetings, the hundreds of door knocks, the huge turnouts at public meetings and city hall. Vernis points out that municipal elections are coming up in the fall. While he doesn’t plan to run again, he says he knows that if the city hasn’t fixed the water by then, water will be the number one issue that brings voters to the polls in Three Rivers now.

“We really did something here,” says Casey. “It’s a story of persistence.”

She pauses for a moment, thinking. Then she adds: “But it’s not over until our water comes out clear and we can drink it again.”

“It’s a story of persistence.”

Words to live, love, and lock horns by.

Gwen, you keep writing about places I've been to. It's almost like you're visiting my past life.